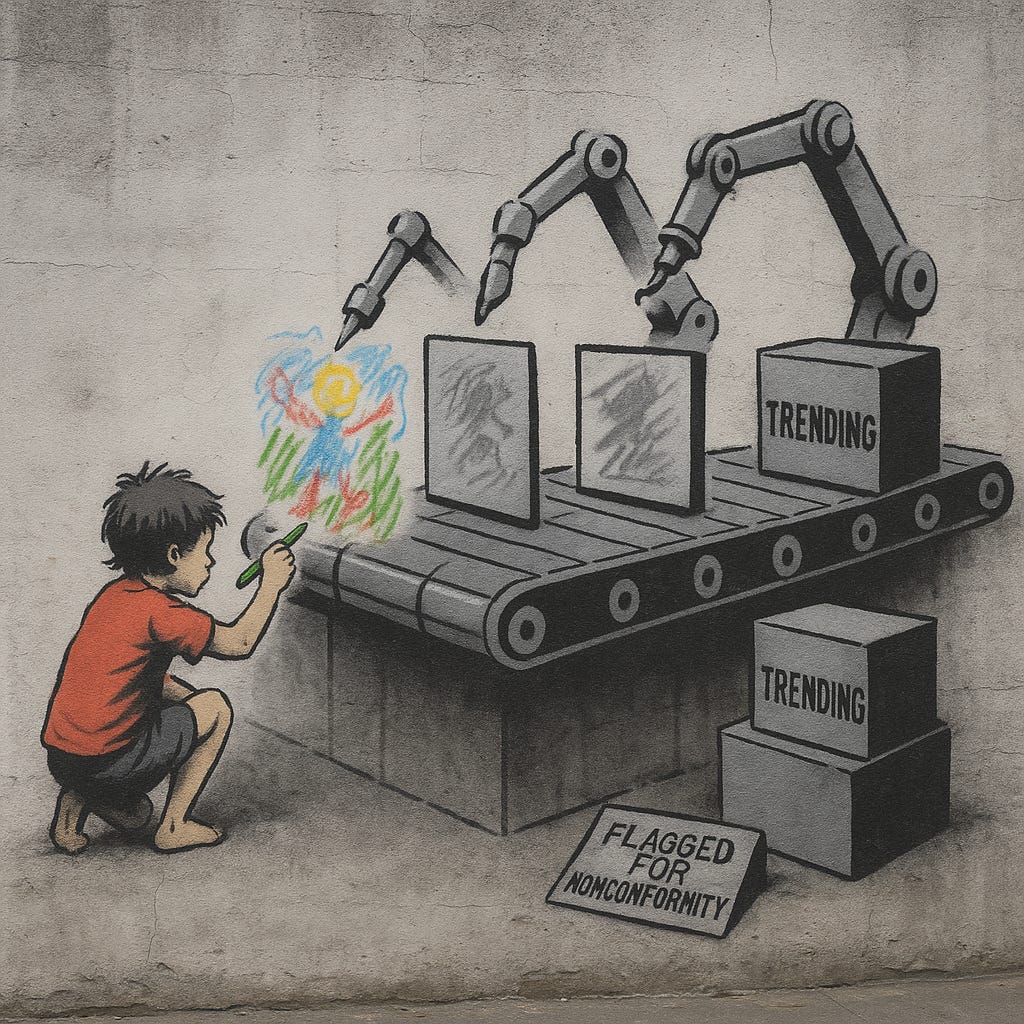

A plea for preserving the messy, explosive, and utterly human art of putting new ideas on paper while the robots hum beside us.

By: R. W. Chapman II

Welcome to our not-so-brave new world.

Predictive text mass-produces prose, and arguments are stitched together by large language models. Originality remains obscure, and the most clickable copy gets the praise.

The distinctive fingerprints of human imagination fade into the smooth plastic of algorithmic sameness. Persistent reliance on AI writing tools will erode the very faculties that make writing worth doing—creativity, spontaneity, and the spark of intellectual risk-taking.

If we allow that erosion to continue unchecked, law, literature, scholarship, and public discourse will congeal into an echo chamber of recycled tropes, half-remembered clichés, and comforting but stagnant copies of copies. The antidote is not to abandon AI, but to renegotiate our relationship with it: to use the machine as a whetstone for thought rather than a substitute for thinking.

Pre-Dawn Reminiscing

Herman Melville began Moby-Dick with “Call me Ishmael,” a line so sparse it slices open the page. Now imagine Melville armed with ChatGPT, churning through hundreds of candidate openers and selecting the statistically safest. We might have received “My name is Ishmael, and this story concerns a whale.” Competent, dull, scrap-able. The horror is not that AI will write bad novels but that it will write acceptable ones—slick enough to coast through an editor’s Friday afternoon slush pile, neutral enough to offend no algorithm, new enough to disguise the fact that it is old.

In the courtroom, the stakes are higher. Creativity births doctrinal leaps: Brandeis’s expectation-of-privacy theory in Olmstead, Thurgood Marshall’s equal-protection artillery in Brown, Antonin Scalia’s Heller originalism. Each of those arguments was, at the moment of deployment, improbable. Software trained to forecast the average of historical briefs would never have surfaced them. Teaching fledgling lawyers to rely on predictive text is the surest way to guarantee that no future Brandeis will bother squeezing that far outside the probability distribution.

Historians of science tell similar stories. Paradigm-smashing insights—the heliocentric model, the double helix, CRISPR—often gestate in eccentric notebooks, marginalia, bar napkin scribbles, places where the thinker wrestles alone with contradictions. AI can accelerate literature reviews, but put it in charge of the next hypothesis and it will anchor to yesterday’s data set. Novelty, by definition, has no training corpus.

Talk to any trial lawyer who cut their teeth before Westlaw, and you will hear stories of legal briefs that sang—idiosyncratic turns of phrase, daring analogies, footnotes that moon-walked through history. Today’s filings often read like they rolled off the same factory belt: identical headings, identical “Argument” sections, identical pleas for “such other relief as this Court deems just and proper.” That monotony predates ChatGPT, but with AI monotony is assured. Humans, when feeling rushed, are happy to let the template stand. A language model does not protest; it merely calculates the most probable continuation.

Creativity withers under such conditions, and we have data points that suggest the trend long precedes this year’s flurry of AI deployments. Kyung Hee Kim’s landmark analysis of 300,000 Torrance Tests found that American creative-thinking scores began a steady decline in 1990, even as IQ scores rose—a phenomenon she christened the “creativity crisis.” [1] Add a pervasive, perfectly polite text generator to the mix and those downward lines risk going from worrisome to vertical.

Your Brain on AI

More alarming still, MIT’s Media Lab has given us a neurological snapshot of what happens when you outsource drafting to a model. In Your Brain on ChatGPT, Nataliya Kosmyna and colleagues strapped EEG headsets to fifty-four volunteers who wrote essays either unaided, with Google, or with ChatGPT. The AI group showed the weakest neural connectivity, the shallowest memory traces, and a progressive decline in engagement over four sessions. [2]

In plainer English: the part of your mind that knits disparate notions into an original sentence starts napping while the bot fills your screen.

If “practice makes perfect,” it also follows that non-practice makes entropy. The decreasing mental load recorded by MIT is the cognitive equivalent of muscle atrophy. Keep lifting with a spotter who does ninety percent of the work and you will soon be unable to bench the bar.

Hyperreality and the Copy-of-a-Copy Problem

“Ask it for something unprecedented and you will get a creative copy of precedent.”

Jean Baudrillard warned in 1981 that Western culture was drifting into hyperreality—a realm where symbols no longer point to real things but to other symbols in an endless funhouse of mirrors. [3] Disney’s Main Street USA, Instagram filters, and canned political slogans are not mirrors of reality; they are simulations of earlier simulations, soothing yet hollow. AI language models are purpose-built to thrive in precisely that environment. They train on oceans of existing text, distill probabilities, and regurgitate the statistically “most likely” sentence fragment to follow whatever you just typed.

I wrote about hypperreality and its dangers in my book: Truth & Persuasion

That mechanism is marvelously useful for autocomplete. It is catastrophically ill-suited to gestating truly new ideas. An LLM cannot be blamed; novelty is not what it promises. A model is a compression engine, deriving the center of gravity of human language as it currently exists. Ask it for something unprecedented and you will often get a fluent restatement of precedent. In hyperreality, the copy is more palatable than the original because it demands less of us. The danger is that we begin to prefer the copy, to find human roughness abrasive, and to sand down every jagged insight until only the familiar template remains.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., writing in Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing (1903), declared that courts “are not, and should not be, the final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations.” [4] Originality, Holmes implied, emerges from the idiosyncratic, the un-algorithmic. Nearly a century later, Feist v. Rural Telephone reaffirmed that even a “minimal degree of creativity” is the irreducible core of copyright. [5] Yet if algorithms begin churning out depositions, marketing copy, even opening statements, where in that deluge does a court locate the spark that deserves protection?

Strip away individuality and the law’s creativity standard collapses into a race to the bottom of boilerplate.

The Cognitive Cost: What the MIT Scans Reveal

The MIT scolds writers for laziness and it quantifies what is lost.

Participants wrote SAT-style essays across three sessions, then some switched conditions in a fourth. The brain-onlycohort displayed the most robust alpha-beta connectivity and the highest self-reported sense of ownership. They could quote their own sentences minutes later. ChatGPT users, by contrast, forgot most of their prose (83 percent could not accurately reproduce a line they had ostensibly authored) and showed attenuated engagement across the default-mode and executive-control networks. [2] In session four, when AI-dependent writers lost their digital co-pilot, their neural signatures plummeted—like a pianist asked to perform after months of letting the player piano do the work.

Critically, the study hints that cognitive debt is cumulative. Each time you defer to the model, you buy convenience on credit; the interest compounds in the form of weaker synaptic firing. Over time, the debt may become so steep that the effort required to craft an original thought feels punitive. Why wrestle with syntax when a bot can serve you a passable paragraph in three seconds?

Law firms already flirt with that temptation. Partner time is expensive; junior associates can feed deposition transcripts into a model and receive a “draft motion” before lunch. But the neural economy does not issue free lunches. The associate who never struggles through a motion for summary judgment may never learn the subtle geometry of precedent needed to win a close case. Creativity in advocacy—finding the unexpected analogue, the out-of-the-box procedural hook—depends on a library of cognitive maneuvers that only grows through grappling, not copy-pasting.

Candidly the MIT Study Has Limitations

The MIT authors caution that their sample size (n = 54) is small, their EEG metrics provisional. Yet their findings triangulate with decades of creativity-score data, the flatline trend of original patents per capita, and anecdotal evidence from editors who increasingly field near-identical submissions.

Kyung Hee Kim found that the most dramatic drop in creative-thinking occurred among K-3 students—exactly the cohort now learning to type prompts before they learn cursive. [1]

Patent originality scores, after rising for a century, plateaued in the mid-2000s and have dipped slightly since 2015, according to USPTO longitudinal studies. [6]

Statistics are blunt instruments, but when multiple gauges blink red, prudence says investigate.

Toward a Renaissance of Human Creativity

Despair is a lazy critic’s refuge. The solution is neither a neo-Luddite bonfire of laptops nor a naïve faith that “the market will fix it.” What we need is a forced friction strategy—deliberate design choices that make it easier to think alongside AI but harder to abdicate thinking.

Creative Fasting. Just as intermittent fasting re-sensitizes the palate, periodic abstention from AI hones cognitive appetite. Universities should institute “analog writing days” where students compose essays longhand or on air-gapped devices. Law firms can pilot “draft-from-scratch Fridays,” reserving AI for cite-checking only. The point is to keep the neural circuitry limber.

Model Transparency Mandates. Require AI systems to watermark outputs and expose provenance layers. A lawyer who sees, sentence by sentence, that her brief leans 72 percent on 2011 appellate dicta may be jolted into injecting her own analysis. Watermarks also give judges and editors a metric for discounting formulaic prose.

Reverse Turing Workshops. In these writing labs, humans attempt to sound less like an AI—rewarding unexpected metaphors, asymmetric arguments, leaps of logic that a probability-smoothing engine would shy from. Such exercises gamify originality and train practitioners to hear the dull hum of homogenization before it infects their style.

Cross-Domain Sabbaticals. Encourage professionals to spend slices of the workweek in disciplines far from their own. A patent attorney who audits a jazz-improvisation class may rewire association networks that no LLM could have predicted. Serendipity is the sworn enemy of hyperreality.

Policy Nudges for Human Authorship. Courts, journals, and publishers can emulate the music industry’s liner-note ethic by asking for “percentage of AI assistance” disclosures. Visibility exerts social pressure: no novelist wants to admit her book is eighty percent remix.

Finally, we must revive a cultural ethic that prizes difficulty as a crucible for insight. The contemporary obsession with frictionless productivity mistakes speed for value. Yet history’s most durable works are often the slowest to gestate. If large language models reclaim all the tedium, the residue left to human beings will be—paradoxically—terrifically boring. The true opportunity is to re-allocate drudgery without outsourcing originality: let AI fetch the precedent while the attorney crafts the daring analogy; let AI summarize the medical literature while the researcher dreams up the impossible experiment.

The Edge of the Unwritten

Every technology reshapes the craft of writing. The printing press demoted the scribe; the typewriter dethroned the quill; the word processor made revision infinite. But none of those tools tried to think for the writer. Generative AI is different. It flatters us with priestly incantations of “creativity on demand” while quietly retraining our brains to settle for the mathematically average. That bargain may feel benign today—our emails are more polished, our briefs more coherent. The bill arrives later, when we reach for a thought that has never been expressed and discover that the neurological muscle we once used for lifting originality has atrophied.

We have time to change course. We can cultivate practices that keep the human writer at the center and the algorithm at the periphery, like a seasoned research assistant who never sleeps but also never composes the thesis statement. The choice is stark: embrace convenience and drift into a culture of infinite repetition, or re-embrace the unpredictability of human authorship and keep the frontier of the unwritten alive. The pen is still in our hand—but only if we resist the temptation to let the machine finish the sentence.

Footnotes

[1] Kyung Hee Kim, “The Creativity Crisis: The Decrease in Creative Thinking Scores on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking,” Creativity Research Journal 23, no. 4 (2011): 285-295.

[2] Nataliya Kosmyna et al., “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task,” MIT Media Lab preprint, arXiv:2506.08872 (June 2025).

[3] Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation (Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1981); English trans. by Sheila Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994).

[4] Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., 188 U.S. 239 (1903).

[5] Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991).

[6] U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, “Patenting by Organizations, Patenting Indices, and Patent Technology Categories, 1976-2023,” Annual Report series (Arlington, VA: USPTO, 2024).

[7] Jaime Smith, “ChatGPT May Be Eroding Critical Thinking Skills, According to a New MIT Study,” Time Magazine, 18 June 2025.

Dear Ron,

Your essay “Writing is Dead” struck me like thunder. Very thought provoking and well written!

What you wrote about AI flattening originality and undermining creativity isn’t abstract—it resonates deeply. I’ve been advocating for a man whose life was derailed in a courtroom where truth had to fight harder than it should. I’ve followed a trial marked by rehearsed narratives and the kind of performative tactics that distract from substance. It often felt like the process favored appearance over reality—form over fairness.

You’re absolutely right: real advocacy isn’t mass-produced. It’s discovered. It’s fought for. It lives in the contradictions and the persistence of those who refuse to be predictable or politically convenient. (The 6th Circuit judges, hopefully, will continue on this vein)

What worries me most is not that AI will produce dull legal writing—but that courts might start expecting only that. That creativity and conscience in advocacy will be treated as inefficiencies rather than necessities. I’ve seen the cost when truth isn’t given room to breathe.

Thank you for reminding us what’s at stake. I don’t want a justice system that prizes efficiency over truth. I want one that still makes space for the improbable—because justice often lives there.

With gratitude and resolve,

Caroline J. Connor, R.N., B.S.N.

Advocate in the fight for Dr. Lawrence Sherman’s exoneration and admirer of your work.

Writing is NOT dead as long as you're the one writing. Nicely "done".